This is the speech Max Liu gave at Percona Live Open Source Database Conference 2016.

The slides are here.

- Speaker introduction

- Why another database?

- What to build?

- How to design?

- How to develop

- How to test?

- The future plan

Speaker introduction

First, about me. I am an infrastructure engineer and I am also the CEO of PingCAP. Currently, my team and I are working on two open source projects: TiDB and TiKV. Ti is short for Titanium, which is a chemical element known for its corrosion resistance and it is widely used in high-end technologies.

So today we will cover the following topics:

- Why another database?

- What kind of database we want to build?

- How to design such a database, including the principles, the architecture, and design decisions?

- How to develop such a database, including the architecture and the core technologies for TiKV and TiDB?

- How to test the database to ensure the quality and stability?

Why another database

Before we start, let’s go back to the very beginning and ask yourself a question: Why another database. We all know that there are many databases, such as the traditional Relational database and NoSQL. So why another one?

- Relational databases like MySQL, Oracle, PostgreSQL, etcetera: they are very difficult to scale. Even though we have sharding solutions, YouTube/vitess, MySQL proxy, but none of them supports distributed transactions and cross-node join.

- NoSQL like HBase, MongoDB, and Cassandra: They scale well, but they don’t support SQL and consistent transactions.

- NewSQL, represented by Google Spanner and F1, which is as scalable as NoSQL systems and it maintains the ACID transactions. That’s exactly what we need. Inspired by Spanner and F1, we are making a NewSQL database. Of course, it’s open source.

What to build?

So we are building a NewSQL database with the following features:

- First of all, it supports SQL. We have been using SQL for decades and many of our applications are using SQL. We cannot just give it up.

- Second, it must be very easy to scale. You can easily increase the capacity or balance the load by adding more machines.

- Third, it supports ACID transaction, which is one of the key features of relational database. With a strong consistency guarantee, developers can write correct logic with less code.

- Last, it is highly available in case of machine failures or even downtime of an entire data center. And it can recover automatically.

In short, we want to build a distributed, consistent, scalable, SQL Database. We name it TiDB.

How to design?

Now we have a clear picture of what kind of database we want to build, the next step is how, how to design it, how to develop it and how to test it. In the next few slides, I am going to talk about how to design TiDB.

In this section, I will introduce how we design TiDB, including the principles, the architecture and design decisions.

The principles or the philosophy

Before we design, we have several principles or philosophy in mind:

- TiDB must be user-oriented.

- It must ensure that no data is ever lost and the system can automatically recover from machine failures or even downtime of the entire datacenters.

- It should be easy to use.

- It should be cross-platform and can run on any environment, no matter it’s on premise, cloud or container.

- As an open source project, we are dedicated to being an important part of the big community through our active engagement, contribution and collaboration.

- We need TiDB to be easy to maintain so we chose the loose coupling approach. We design the database to be highly layered with a SQL layer and a Key-Value layer. If there is a bug in SQL layer, we can just update the SQL layer.

- The alternatives: Although our project is inspired by Google Spanner and F1, we are different from those projects. When we design TiDB and TiKV, we have our own practices and decisions in choosing different technologies.

Disaster recovery

The first and foremost design principle is to build a database where no data is lost. To ensure the safety of the data, we found that multiple replicas are just not enough and we still need to keep Binlog in both the SQL layer and the Key-Value layer. And of course, we must make sure that we always have a backup in case the entire cluster crashes.

Easy to use

The second design principle is about the usability. After years of struggling among different workarounds and trade-offs, we are fully aware of the pain points of the users. So when it comes to us to design a database, we are going to make it easy to use and there should be no scary sharding keys, no partition, no explicit handmade local index or global index, and making scale transparent to the users.

Cross-platform

The database we are building also needs to be cross-platform. The database can run on the on premise devices. Here is a picture of TiDB running on a Raspberry Pi cluster with 20 nodes.

It can also support the popular containers such as Docker. And we are making it work with Kubernetes. Of course, it can be run on any cloud platform, whether it’s public, private or hybrid.

The community and ecosystem

The next design principle is about the community and ecosystem. We want to stand on the shoulders of the giants instead of creating something new and scary. TiDB supports MySQL protocol and is compatible with most of the MySQL drivers (ODBC, JDBC) and SQL syntax, MySQL clients and ORM, and the following MySQL management tools and bench tools.

etcd

etcd is a great project. In our Key-Value store, TiKV, which I will dive deep into later, we have been working with the etcd team very closely. We share the Raft implementation, and we do code reviews on Raft module for each other.

RocksDB

RocksDB is also a great project. It’s mature, fast, tunable, and widely used in very large scale production environments, especially in facebook . TiKV uses RocksDB as it’s local storage. While we were testing it in our system, we found some bugs. The RocksDB team fixed those bugs very quickly.

Namazu

A few months ago, we need a tool to simulate slow, unstable disk, and the team member found Namazu. But at that time, Namazu didn’t support hooking fsync. When the team member raised this request to their team, they responded immediately and implement the feature in just a few hours and they are very open to implement other features as well. We are deeply impressed by their responsiveness and their efficiency.

Rust community

The Rust community is amazing. Besides the good developing experience of using Rust, we also build the Prometheus driver in Rust to collect the metrics.

We are so glad to be a part of this great family. So many thanks to the Rust team, gRPC, Prometheus and Grafana.

Spark connector

We are using the Spark connector in TiDB. TiDB is great for small or medium queries and Spark is better for complex queries with lots of data. We believe we can learn a lot from the Spark community too, and of course we would like to contribute as much as possible.

So overall, we’d like to be a part of the big open source community and would like to engage, contribute and collaborate to build great things together.

Loose coupling – the logical architecture

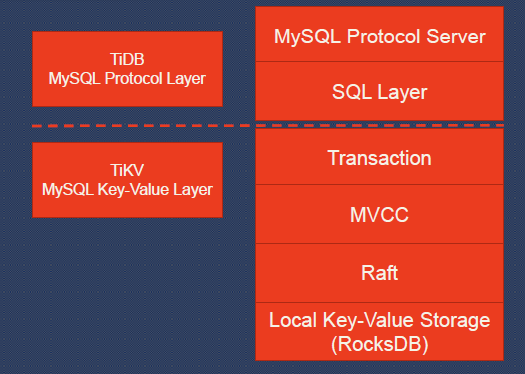

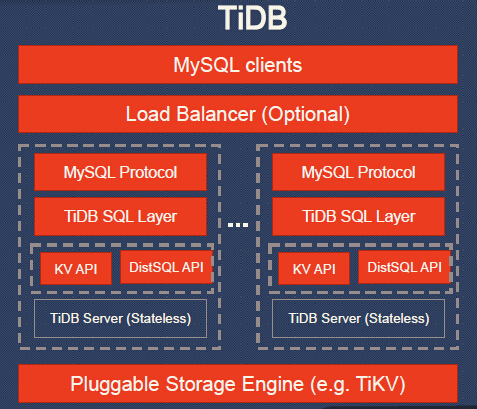

This diagram shows the logical architecture of the database.

As I mentioned earlier about our design principle, we are adopting the loose coupling approach. From the diagram, we can see that it is highly-layered. We have TiDB to work as the MySQL server, and TiKV to work as the distributed Key-Value layer. Inside TiDB, we have the MySQL Server layer and the SQL layer. Inside TiKV, we have transaction, MVCC, Raft, and the Local Key-Value Storage, RocksDB.

For TiKV, we are using Raft to ensure the data consistency and the horizontal scalability. Raft is a consensus algorithm that equals to Paxos in fault-tolerance and performance. Our implementation is ported from etcd, which is widely used, very well tested and highly stable. I will cover the technical details later.

From the architecture, you can also see that we don’t have a distributed file system. We are using RocksDB as the local store.

The alternatives

In the next few slides, I am going to talk about design decisions about using the alternative technologies compared with Spanner and F1, as well as the pros and cons of these alternatives.

Atomic clocks / GPS clocks VS TimeStamp Allocator

If you’ve read the Spanner paper, you might know that Spanner has TrueTime API, which uses the atomic clocks and GPS receivers to keep the time consistent between different data centers.

The first alternative technology we chose is to replace the TrueTime API with the TimeStamp Allocator. It goes without any doubt that time is important and that Real time is vital in distributed systems. But can we get real time? What about clock drift?

The sad truth is that we can’t get real time precisely because of clock drift, even if we use GPS or Atomic Clocks.

In TiDB, we don’t have Atomic clocks and GPS clocks. We are using the Timestamp Allocator introduced in Percolator, a paper published by Google in 2006.

The pros of using the Timestamp Allocator are its easy implementation and no dependency on any hardware. The disadvantage lies in that if there are multiple datacenters, especially if these DCs are geologically distributed, the latency is really high.

Distributed file system VS RocksDB

Spanner uses Colossus File System, the successor to the Google File System (GFS), as its distributed file system. But in TiKV, we don’t depend on any distributed file system. We use RocksDB. RocksDB is an embeddable persistent key-value store for fast storage. The primary design point for RocksDB is its great performance for server workloads. It’s easy for tuning Read, Write and Space Amplification. The pros lie in that it’s very simple, very fast and easy to tune. However, it’s not easy to work with Kubernetes properly.

Paxos VS Raft

The next choice we have made is to use the Raft consensus algorithm instead of Paxos. The key features of Raft are: Strong leader, leader election and membership changes. Our Raft implementation is ported from etcd. The pros are that it’s easy to understand and implement, widely used and very well tested. As for Cons, I didn’t see any real cons.

C++ VS Go & Rust

As for the programming languages, we are using Go for TiDB and Rust for TiKV. We chose Go because it’s very good for fast development and concurrency, and Rust for high quality and performance. As for the Cons, there are not as many third-party libraries.

That’s all about how we design TiDB. I have introduced the principles, the architecture, and design decisions about using the alternative technologies. The next step is to develop TiDB.

How to develop

In this section, I will introduce the architecture and the core technologies for TiKV and TiDB.

The architecture

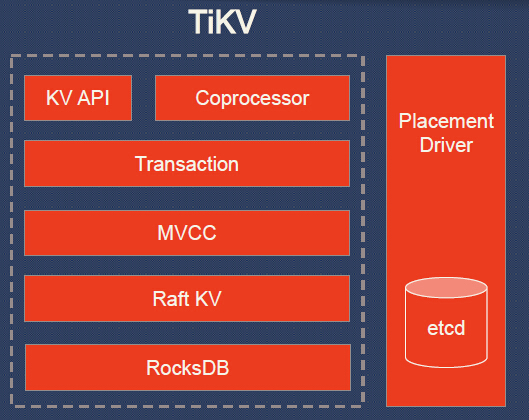

About TiKV architecture: Let’s take a look from the bottom.

- The bottom layer, RocksDB.

- The next layer, Raft KV, it’s a distributed layer.

- MVCC, Multiversion concurrency control. I believe many of you are pretty familiar with MVCC. TiKV is a multi-versioned database. MVCC enables us to support lock-free reads and ACID transactions.

- Transaction: The transaction model is inspired by Google’s Percolator. It’s mainly a two-phase commit protocol with some practical optimizations. This model relies on a timestamp allocator to assign monotone increasing timestamp for each transaction, so the conflicts can be detected. I will cover the details later.

- KV API: it’s a set of programming interfaces and allows developers to put or get data.

- Placement Driver: Placement driver is a very important part, and it helps to achieve geo-replication, horizontal scalability and consistent distributed transactions. It’s kind-of the brain of the cluster.

About the TiDB architecture:

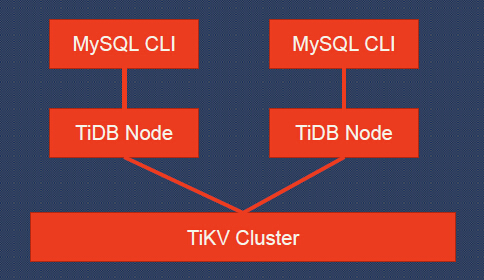

- MySQL clients: The top layer is a set of MySQL clients. These clients send requests to the next layer. You can still use any MySQL driver that you are already familiar with.

- Load Balancer: This is an optional layer. Such as HAProxy or LVS.

- TiDB Server: It’s stateless, and a client may connect to any TiDB server. Within the TiDB server, the top layer is MySQL Protocol, it provides MySQL protocol support; the next layer is SQL optimizer, which is used to translate MySQL requests to TiDB SQL plan.

- The bottom layer is KV API and Distributed SQL API. If the lower level storage engine supports coprocessor, TiDB SQL Layer will use DistSQL API, which is much more efficient than KV API. TiDB supports pluggable storage engines. We recommend TiKV as the default storage engine.

TiKV core technologies

Let’s take a look at the TiKV core technologies.

We build TiKV to be a distributed key-value layer to store data.

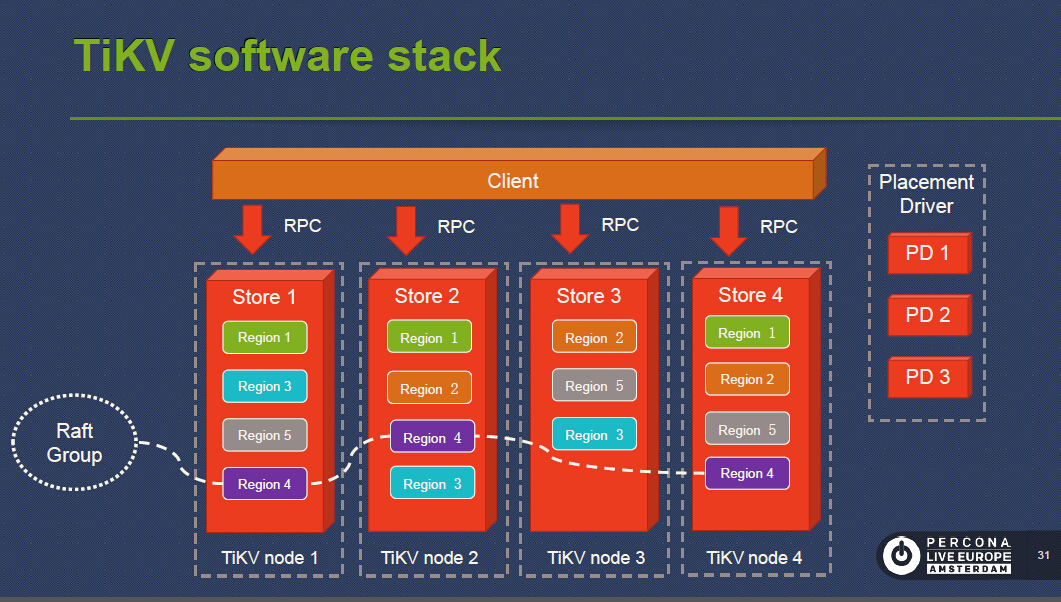

TiKV software stack

Let’s take a look at the software stack.

First, we can see that there is a client connecting to TiKV. We also have several nodes. And within each node, we have stores, one per physical disk. Within each store, we have many regions. Region is the basic unit of data movement and is replicated by Raft. Each region is replicated to several nodes. A Raft group consists of the replicas of one Region. And region is more like a logical concept, in a single store, many regions may share the same RocksDB instance.

Placement Driver

About Placement Driver, this concept comes from the original paper of Google Spanner. It provides the God’s view of the entire cluster. It has the following responsibilities:

- Stores the metadata: Clients have cache of the placement information of each region.

- Maintains the replication constraint, 3 replicas by default.

- Handles the data movement to balance the workload automatically. When placement driver notices that the load is too high, it will rebalance the data or transfer the leadership by using Raft

And thanks to Raft, within itself, Placement Driver is a cluster too and it is also highly available.

Raft

In TiKV, we use the Raft for scaling and replication. We have multiple Raft groups. Workload is distributed among multiple regions. There could be millions of regions in one big cluster. Once a region is too large, it will be split into two smaller regions, just like cell division.

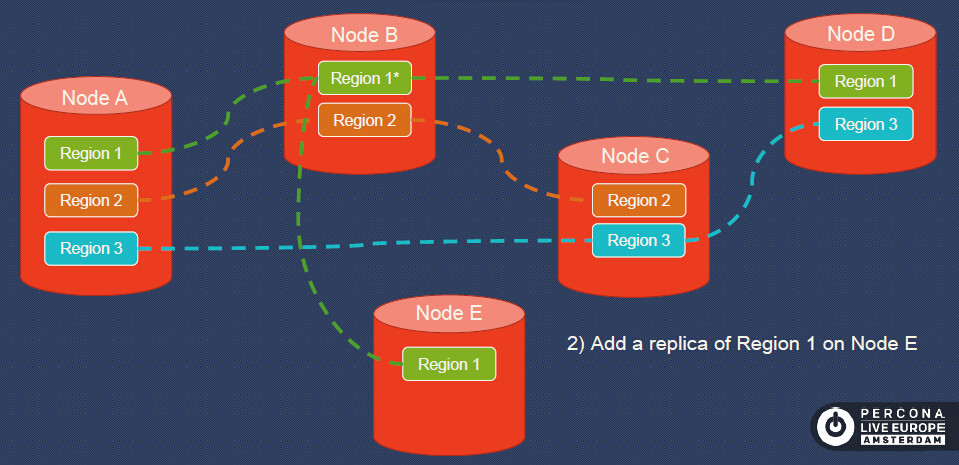

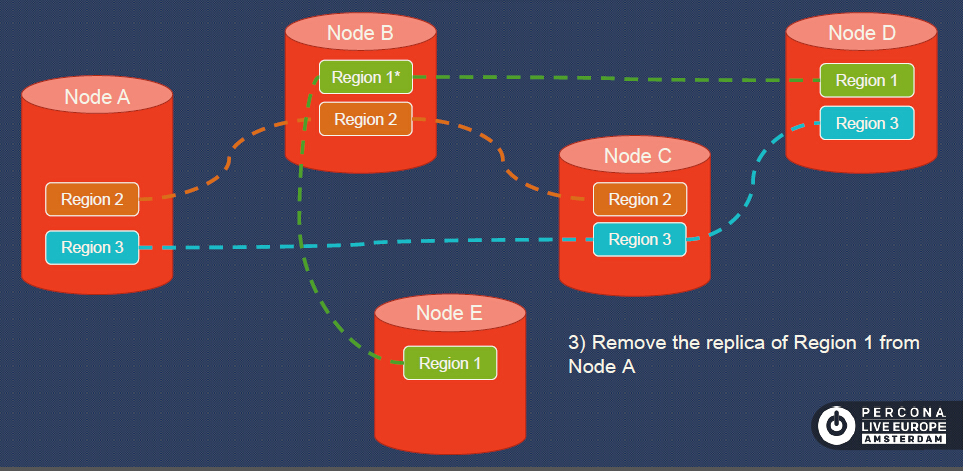

In the next few slides, I will show you the scaling-out process.

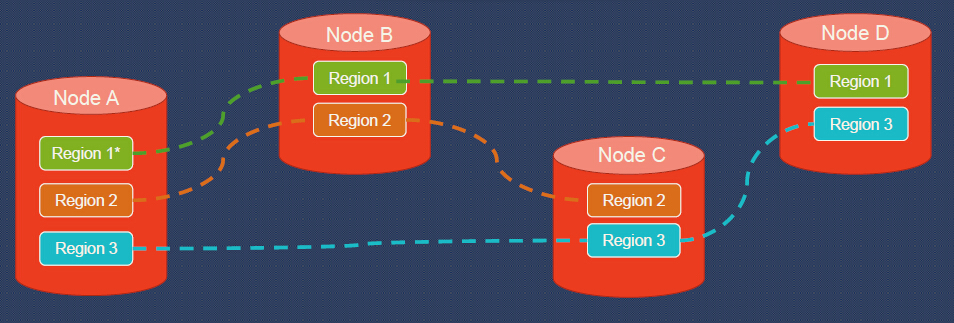

Scale-out

In this diagram, we have 4 nodes, namely Node A, Node B, Node C, and Node D. And we have 3 regions, Region 1, Region 2 and Region 3. We can see that there are 3 regions on Node A.

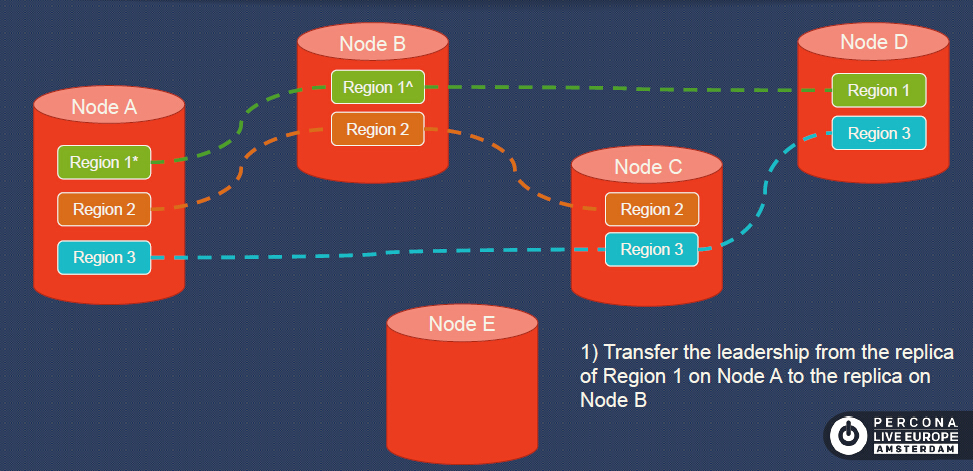

To balance the data, we add a new node, Node E. The first step we do is to transfer the leadership from the replica of Region 1 on Node A to the replica on Node B.

Step 2, we add a Replica of Region 1 to Node E.

Step 3, remove the replica of Region 1 from Node A.

Now the data is balanced and the cluster scales out from 4 nodes to 5 nodes.

This is how TiKV scales out. Let’s see how it handles auto-failover.

MVCC

- Each transaction sees a snapshot of the database at the beginning time of this transaction. Any changes made by this transaction will not be seen by other transactions until the transaction is committed.

- Data is tagged with versions in the following format: Key_version: value.

- MVCC also ensures Lock-free snapshot reads.

Transaction

These are Transaction APIs. As a programmer, I want to write code like this:

txn := store.Begin() // start a transaction

txn.Set([]byte(“key1”), []byte(“value1”))

txn.Set([]byte(“key2”), []byte(“value2”))

err = txn.Commit() // commit transaction

if err != nil {

txn.Rollback()

}

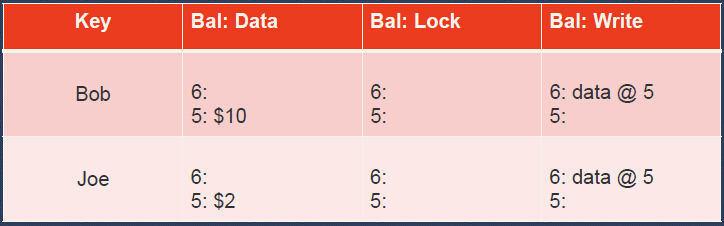

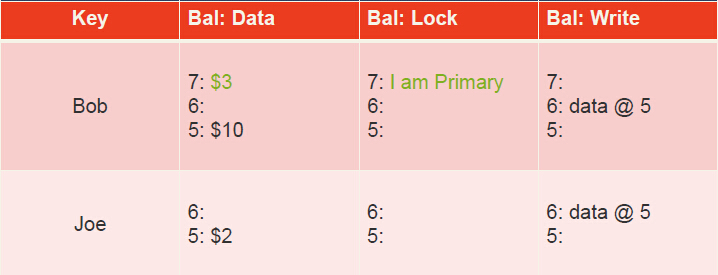

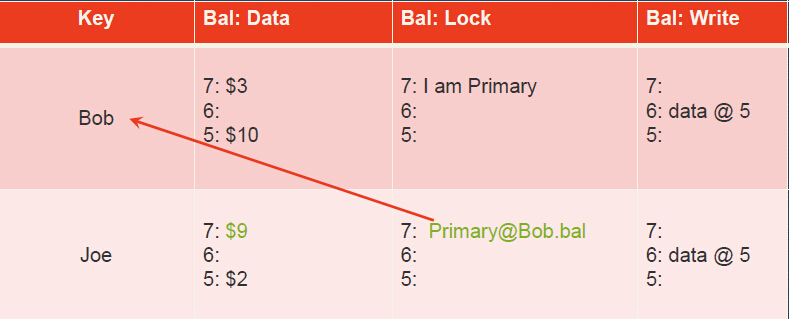

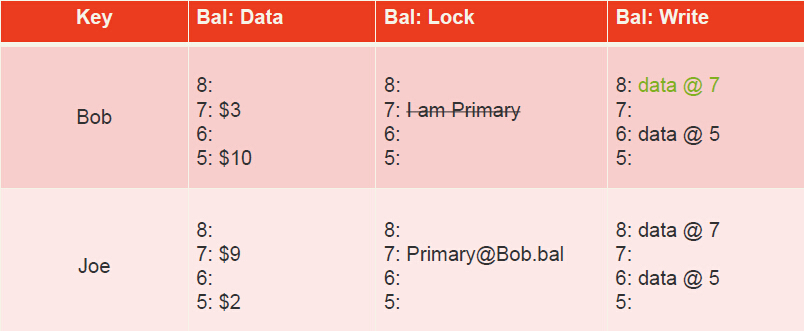

Speak of Transaction, It’s mainly a two-phase commit protocol with some practical optimizations. In the transaction model, there are 3 column families, namely, cf:lock, cf:write and cf:data.

- cf: lock: An uncommitted transaction is writing this cell and contains the location/pointer of primary lock. For each transaction, we choose a primary lock to indicate the state of the transaction.

- cf: write: It stores the commit timestamp of the data

- cf: data: Stores the data itself

Let’s see an example: If Bob wants transfer 7 dollars to Joe.

-

Initial state: Joe has 2 dollars in his account, Bob has 10 dollars.

-

The transfer transaction begins by locking Bob’s account by writing the lock column. This lock is the primary for the transaction. The transaction also writes data at its start timestamp, 7.

-

The transaction now locks Joe’s account and writes Joe’s new balance. The lock is secondary for the transaction and contains a reference to the primary lock; So we can use this secondary lock to find the primary lock.

-

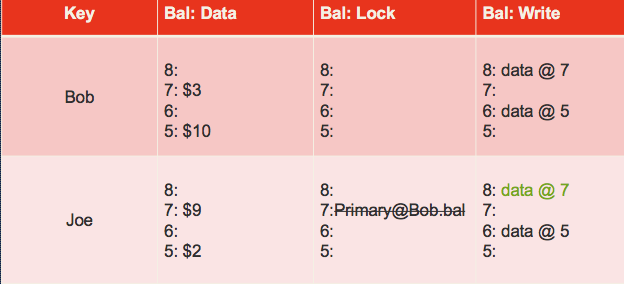

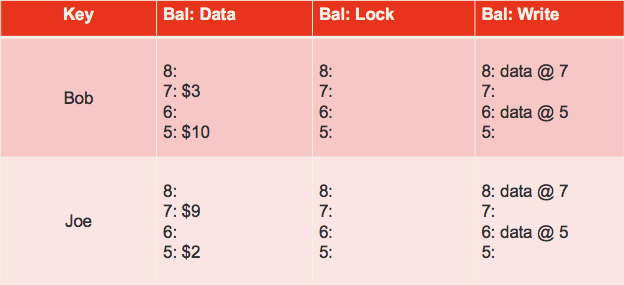

The transaction has now reached the commit point: it erases the primary lock and replaces it with a write record at a new timestamp (called the commit timestamp): 8. The write record contains a pointer to the timestamp where the data is stored. Future readers of the column “bal” in row “Bob” will see the value $3.

-

The transaction completes by adding write records and deleting locks at the secondary cells. In this case, there is only one secondary: Joe.

So this is how it looks like when the transaction is done.

TiDB core technologies

That’s it about the TiKV core technologies. Let’s move on to TiDB.

TiDB has a protocol layer that is compatible with MySQL. And it will do the following things:

- Mapping table data to Key-Value store to connect to the key-value storage engine.

- Predicate push-down, to accelerate queries

- Online DDL

Mapping table data to Key-Value store

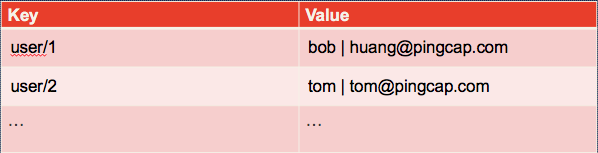

Let’s use an example to show how a SQL table is mapped to Key-Value pairs.

If we have a simple user table in database. It has 2 rows and 3 columns: user id, name and email. And user id is the primary key.

INSERT INTO user VALUES (1, "bob", "huang@pingcap.com");

INSERT INTO user VALUES (2, "tom", "tom@pingcap.com");

If we map this table to key-value pairs, it should be put in the following way.

Of course, TiDB supports secondary index. It’s a global index. TiDB puts data and index updates into the same transaction, so all the indexes in TiDB are transactional and fully consistent. And it’s transparent to the users.

Indexes are just key-value pairs that the values point to the row key. After we create indexes for the user name, the key-value storage looks like this:

The key of the index consists of two parts: the name and the user id as the suffix. So here “bob” is the name, and 1 is the user id, and the value points to the row key.

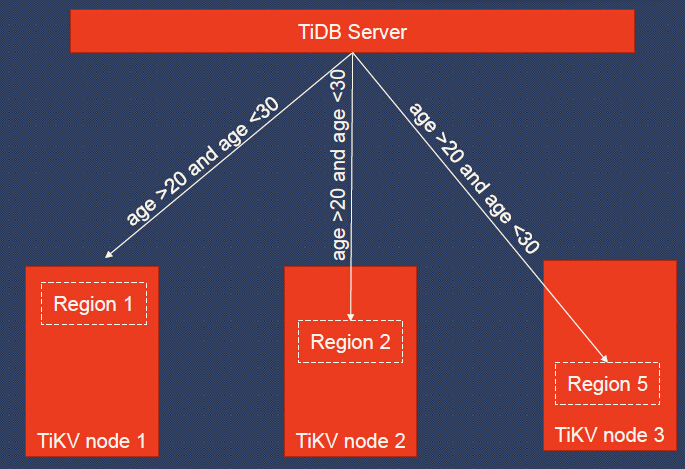

Predicate push-down

For some operations like count some columns in a table, TiDB pushes down these operations to the corresponding TiKV nodes, the TiKV nodes do the computing and then TiDB merges the final results. This diagram shows the process of a simple predicate push-down.

Schema changes

This slide is about schema changes. Why online schema change is a must-have feature? It’s because we need the full data availability all the time and minimal performance impact so that the ops people can have a good-night’s sleep.

Something the same as Google F1

The main features of TiDB that impact schema changes are:

- Distributed

- An instance of TiDB consists of many individual TiDB servers

- Relational schema

- Each TiDB server has a copy of a relational schema that describes tables, columns, indexes, and constraints.

- Any modification to the schema requires a distributed schema change to update all servers.

- Shared data storage

- All TiDB servers in all datacenters have access to all data stored in TiKV.

- There is no partitioning of data among TiDB servers.

- No global membership

- Because TiDB servers are stateless, there is no need for TiDB to implement a global membership protocol.This means there is no reliable mechanism to determine currently running TiDB servers, and explicit global synchronization is not possible.

Something different from Google F1

But TiDB is also different from Google F1 at the following aspects:

- TiDB speaks MySQL protocol

- The statements inside of a single transaction cannot cross different TiDB servers

One more thing before schema change

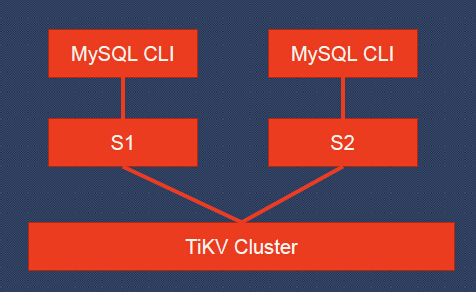

One more thing before schema change. Let’s take a look at the big picture of SQL in TiDB:

Here is an overview of a TiDB instance during a schema change:

Schema change: Adding index

So let’s see how the schema changes when it comes to adding an index.

Servers using different schema versions may corrupt the database if we are not careful.

Consider a schema change from schema S1 to schema S2 that adds index I on table T. Assume two different servers, M1 and M2, execute the following sequence of operations:

-

Server M2, using schema S2, inserts a new row r to table T. Because S2 contains index I, server M2 also adds a new index entry corresponding to r to the key–value store.

-

Server M1, using schema S1, deletes r. Because S1 does not contain I, M1 removes r from the key–value store but fails to remove the corresponding index entry in I.

The second delete corrupts the database. For example, an index-only scan would return incorrect results that include column values for the deleted row r.

Schema states

Basically schema changes is a multiple state multiple phase protocol. There are two states which we consider to be non-intermediate: absent and public.

There are two internal, intermediate states: delete-only and write-only

Delete-only: A delete-only table, column, or index cannot have their key–value pairs read by user transactions and

-

If E is a table or column, it can be modified only by the delete operations.

-

If E is an index, it is modified only by the delete and update operations. Moreover, the update operations can delete key–value pairs corresponding to updated index keys, but they cannot create any new one.

For the write-only state, it is defined for columns and indexes as follows:

A write-only column or index can have their key–value pairs modified by the insert, delete, and update operations, but none of their pairs can be read by user transactions.

Schema change flow: Add index

There are 4 steps to add an index.

Step 1, we mark the state to delete-only, wait for one schema lease, after all of the TiDB servers reach the same state, we move to

Step 2, mark the state as write-only, wait for one schema lease,

Step 3, mark the state as Fill Index and we start a mapreduce job to fill the index. After finishing the index filling job, we wait for one schema lease,

then Step 4, switch to the final state where all of the new queries can use the newly added index.

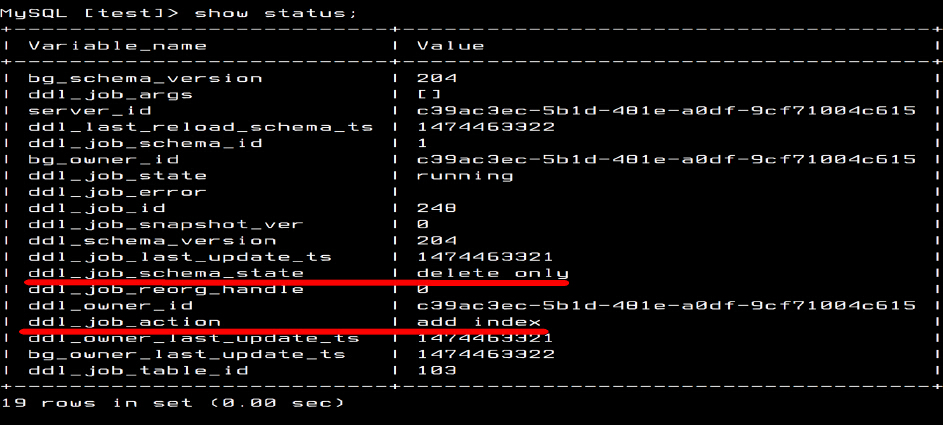

TiDB: status of Adding index (delete-only)

Here is one of the screenshots for adding an index.

We can use any MySQL client to query the status of the online DDL job. Just simply run the “show status” statement and we can see that the current state is “delete-only” as I highlighted and that the action is “add index”. There is some other information such as who is doing the DDL job, the state of the current job and the current schema version.

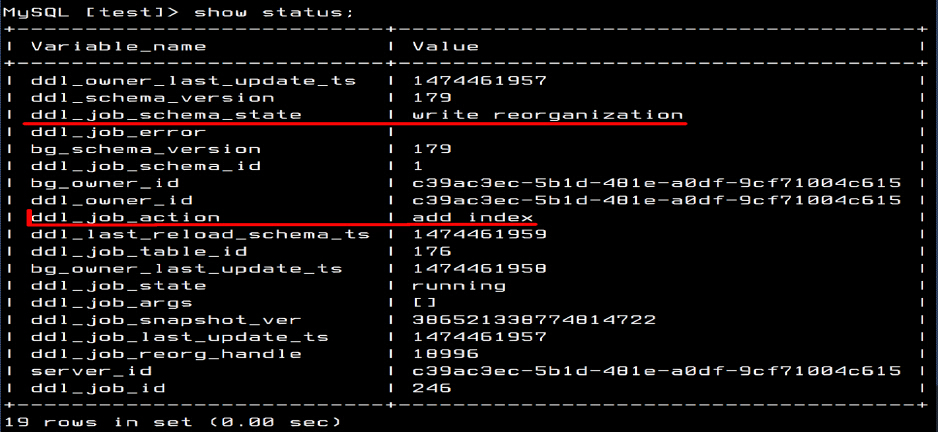

TiDB: status of Adding index (add index)

This screenshot shows that the current state is “write reorganization” as I highlighted.

How to test?

In this section, I will introduce how we are testing the system.

- The test cases come from community. There are a lots of test cases in MySQL drivers/connectors, ORMs and applications.

- Fault injection is performed on both hardware and software to increase the test coverage.

- About the network, we simulate the latency, failure, partition to detect if there are bugs in our database when the network is not reliable.

- We use Jepsen and Namazu for distributed testing.

The future plan

Here is our future plan:

- We are planning to use GPS and Atomic clocks in the future.

- We are improving our query optimizer to get better and faster query results.

- We will improve the compatibility with MySQL.

- The supports for the JSON and document storage types are also on our roadmap.

- We are planning to support pushing down more aggregation and built-in functions.

- In the future, we will replace the customized RPC implementation with gRPC.

So that’s all. Thank you! Any questions?

TiDB Cloud Dedicated

TiDB Cloudのエンタープライズ版。

専用VPC上に構築された専有DBaaSでAWSとGoogle Cloudで利用可能。

TiDB Cloud Starter

TiDB Cloudのライト版。

TiDBの機能をフルマネージド環境で使用でき無料かつお客様の裁量で利用開始。